This is an excerpt from a paper published by the US Army Sergeants Major Academy as a submission for the General Haines Award for Excellence in Research by CSM Joe Parson, the senior enlisted advisor of the Army Capabilities Integration Center, Fort Eustis, Virginia. This article was in response to a course requirement and completed Oct 15, 2005. This excerpt is reprinted by permission of the author.

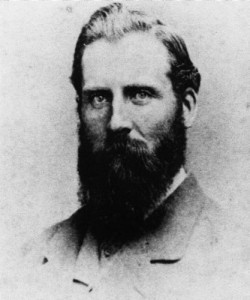

1SG Percival G. Lowe

Few enlisted Soldiers have captured and recorded the experiences and lifestyle of the enlisted Soldier during the nation’s history. One such author is 1SG Percival G. Lowe. Through his journals and later his novel, “Five Years a Dragoon”, he continues to enlighten later generations on the trials and hardship of being a Soldier in the mid 1800’s. His accomplishments and contributions extend beyond the five years he spent in military uniform, through his continued service to the Quartermaster Department and as a civilian.

In order to understand his perspective, you must also understand the individual, his background, and the experiences that made him the Soldier, leader, and person that he was. Percival G. Lowe was born on September 29,1828 in Randolph, Coos County, New Hampshire. His mother, the former Alpha Green was a homemaker and his father Clovis was a merchant, real estate dealer, justice of the peace, and a politician. It is believed the G. in Percival’s name is from his mother’s maiden name (Lowe p. xiii). His immediate family consisted of his parents, sister, and three brothers. For the era, Percival’s family was considered somewhat wealthy although it did not show from their humble living conditions. As a child, Percival had to deal with other children teasing him about his name. To counter this, Percival often went by the nickname P. G. and learned to defend himself at a young age, a skill that would become beneficial later in his life. Although Percival received no formal education, his mother did teach her children how to read and write. At the age of fourteen Percival was sent to live with his uncle in Lowell, Massachusetts. The purpose for his stay was to learn a trade. Percival worked as a newsboy, dry-goods clerk, a sailor for two years, and for a short period studied the daguerreotype business. The daguerreotype, what is now consider the predecessor of the modem photograph, was becoming a thriving industry in the United States at the time.

Percival longed for more excitement and in January of 1846, he set sail again as a crew member of the Jane Howes (Lowe p. xiv). For the next three years, he served as part ofthis crew sailing primarily in the Gulf of Mexico region. During this same period, the Gold Rush of 1848 was at its peak and Percival became interested in the westward movement. Percival’s fascination with the West also grew as he read about Fremont’s expeditions and the writings of Irving, particularly the “Adventures of Captain Bonneville” (Lowe p. xiv). It was his fascination with the West that resulted in his decision to the join the Army. He knew that the majority of the Soldiers currently serving were posted there, and to guarantee a posting in the West he must choose a type of unit that was serving there solely. So, at a Boston recruiting station at the end of the summer of 1849, Lowe joined the 15t Dragoons of the U.S. Army (Johnston p. 84).

Lowe’s training began at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania with a heavily regimented schedule of both mounted and dismounted drill. These drills also familiarized the new recruits on the use of the saber, the musketoon, and the revolver, which were the primary weapons of the Dragoons during this period. His nights consisted of evening mess followed by a short period to care for his horse and equipment then followed by retreat to the barracks. Sundays were strictly for religious services and equipment inspections. One particular Sunday Lowe prepared his equipment display and left to eat breakfast. When he returned his gear was no longer on his bunk and in its place he found a set of gear in total disrepair. Lowe inquired throughout the barracks and was finally informed that a fellow recruit, known as Big Mit, had taken his gear and replaced it with his own. Lowe then went to Big Mit’s bunk and secured his gear. When Big Mit returned he immediately confronted Lowe.

Although Lowe was half his size, it was clear he could stand his own ground when he began to beat Big Mit with the end of his saber. The beating was severe enough to send the big man to the infirmary (Arms). Percival established himself that day in the eyes of his fellow recruits but more importantly, in the eyes of the tougher crowd by demonstrating that he was a force with which to be reckoned. Upon the completion of training, Lowe and 75 other recruits remained at Carlisle Barracks awaiting transportation to their new units out West.

That day soon came when Lowe and the other recruits began their journey. They traveled by horse, foot, wagon, train, and barge where they finally arrived at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas on Christmas Day 1849 and Lowe joined his new unit, B Troop, 1 st Dragoons (Lowe p. 16). It was not long before Lowe realized that his new living conditions were much more austere than his previous post. His Christmas dinner consisted of bread, boiled pork, and coffee. Within the first twenty-four hours, several ofthe new recruits were missing their coats. Some of the rougher individuals in the unit had stolen them in order to buy whiskey, clearly a sign of an undisciplined unit and a fact Lowe would remember and directly influence later in his career.

While at Leavenworth drill continued. The units waited for spring and its fair weather when they would return to the field. Lowe would often trade with the local farmers for fresh vegetables and share them with his fellow Soldiers in order to augment their daily rations. Lowe still had in his possession several hundred dollars from his time serving as a sailor, which made him, unknowingly to the other Soldiers, one of the wealthiest Soldiers in the unit. He often supported the unit by aiding the Quartermaster Sergeant in his purchase of fresh supplies (Arms). Lowe watched and learned quickly. He knew how important it was to maintain his horse and his equipment; these were the essential items that would keep a Soldier alive on the plains. He also learned about the Soldiers in his unit and how to lead them. Due to his natural leadership ability, he was quickly promoted to the rank of Corporal, Sergeant, and ultimately to First Sergeant in June of 1851, just two years after joining the Army (Arms). Promotions during this period were based on vacancies in the unit. As a Soldier left the Army, the Commanding Officer would choose the most eligible Soldier to fill the vacancy regardless of his time in service, it was strictly based on his performance and potential.

As First Sergeant, Lowe was responsible for the daily administrative functions of the unit, such as muster and fatigue details, as well as leading small units during operations in the field. A large portion of his time was spent handling discipline issues. During this period in military history, desertion was fairly common. The primarily reasons a Soldier deserted were the gold rush in the West and the austere living conditions they experienced on the plains. For this reason, 1 SG Lowe and his Noncommissioned Officers instituted the “company court-martial” (Arms). Although the Army did not recognize this process, Lowe’s system did establish a procedure for the NCOs to enforce discipline by punishing Soldiers for minor offenses. This also preserved the careers of many Soldiers and kept discipline issues at the lowest level. Although this practice may have occurred in other units prior to his, 1 SG Lowe is credited for its establishment primarily due to his journals and later his novel which recorded the process he used.

One note of credit to 1 SG Lowe is the fact that throughout his journals and his novel he never specifically named an individual who may have behaved or acted in a manner unbecoming of a Soldier. It is quite possible he did this so families would not feel any repercussion from the Soldier’s actions and would help preserve their dignity. His intent was to record history and not purposely ruin anyone’s future. 1SG Lowe left active military service in 1854. He participated in only sixteen skirmishes with Indians during his military service but this wasn’t the end to his life and experiences on the plains. As he left the military, he was offered the job as the Chief Wagon Master of the Quartermaster Department at Fort Leavenworth, which he graciously accepted. In that capacity, he directly affected numerous events in the nation’s history.

In 1855, Lowe served alongside of Maj. Edmund A. Ogden in the establishment of Fort Riley, Kansas. During a short period, Lowe assumed command of the expedition when Maj. Ogden and several dozen of their men fell ill from a cholera epidemic and later died (Lowe p. 149). Lowe remained in command of the post until Col. Cooke arrived to relieve him, at which time Lowe returned to Fort Leavenworth. It was only a matter ofweeks before Lowe was pushing supplies back out to the troops in support of the Kansas’ Wars of 1856. In 1857, he supported Col. Sumner’s forces during the Cheyenne uprisings along the plains, and in 1858, he pushed supplies and troops out to the Utah Territory in support ofthe Mormon Wars (Connelley p. 1219). In 1859, Lowe decided to leave the military service completely and open his own transportation business.

Finally, at the age of thirty and after spending the last decade of his life devoted to the Army, Lowe opened his own business under the partnership of Clayton, Lowe & Company (Lowe p. 277). A friend of Lowe’s, George W. Clayton provided him with the financial support he needed. Their business was to transport the materials desperately needed for mining operations in the West. Their business prospered and both men amassed a small fortune. During this time, Lowe also married his wife Margaret and built a home at Fort Leavenworth as well as a home in Denver, Colorado. They closed their business at the onset of the Civil War in 1865, at which time he was offered a commission in the U.S. Army. Lowe declined the commission so he could finally spend time with and protect his family during this difficult period. Lowe remained at Fort Leavenworth throughout the remainder of his life.

While a resident of Fort Leavenworth, Lowe served in several government positions within the city, county, and State of Kansas. In 1868, 1869, and 1875 Lowe served as a member of the Leavenworth City Council. From 1876 to 1881, Lowe served as the County Sheriff, and from 1885 to 1889, Lowe also served as a Kansas State Senator (Connelley p. 1219). Lowe’s single greatest contribution to the nation may have occurred in 1906 when his journals were published as his novel “Five Years a Dragoon“. Until that time, the nation’s history had recorded little about the life of the enlisted Soldier through the eyes of a fellow enlisted Soldier.

Lowe’s novel helped to capture a period in the nation’s history when the Army was between conflicts, the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. This was a time when economic prosperity was on the rise and the military was considered fairly unimportant. The Soldiers serving during this period were mostly foreign immigrants from the city or poor farmers from rural areas. Lowe and a few others he described in his novel were the exception. They were an exception that helped maintain order where there previously was none, to build sound cohesive units, and ultimately helped to establish lasting traditions. They also formulated tactics, techniques, and procedures that directly aided the Army in future conflicts such as the Civil War and primarily during the Indian Wars. Lowe’s development and drawings of wagon train tactics were reproduced numerous times and directly influenced the expansion and settlement of the West. Lowe helped to capture the lives and experiences of many national leaders and statesmen, men with such names as; Stuart, Bridger, Carson, Hancock, Haney, Sumner, Cooke, and Emory. These names are synonymous with the expansion ofthe West, the Civil War, and many other facets in the nation’s history. His journals also helped to capture an interesting aspect in the history of the Officer Corps and the use of the brevet rank.

Although it is not common knowledge, the majority of Army officers graduating from the Military Academy during the mid-nineteenth century could not receive a direct commission due to the small size of the Army (Lowe p. xxi). At the time, the Army only consisted of 15 Regiments with just over 10,000 Soldiers (Lowe p. xvi). To manage the dilemma of not enough Officers in uniform and the small yearly allocation of positions, many young officers were “frocked” and received a rank of Brevet Second Lieutenant. In line units, most ofthe Commissioned Officers were assuming duties elsewhere such as a recruiting and finance details. This resulted in many of the Brevet Officers temporarily, if not permanently, assuming their duties and command positions. This made the role of the Noncommissioned Officer within the Army even more important. Brevet rank was common throughout the Officer Corps particularly during the Civil War. Many General Officers during the Civil War held a brevet rank primarily because their State would promote them while the Army would or could not due to positions being unavailable. These are just a few of the details that his journals and novel helped to capture and preserve from the Army’s history.

Percival G. Lowe died on the 5th of March 1908 while visiting family and friends in San Antonio, Texas. He was laid to rest with his wife in the military cemetery at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Although his service to the military was only five years, he spent over fifty years in service to his country in various positions. Today, his novel continues to share his memory and his experiences.

Oscar Wilde, an Irish poet, once said, “Anyone can make history, but only a great man can write it” (Wilde). Lowe demonstrated that he was a man of such caliber. His unwavering character and professionalism resonate throughout his novel and the events of his life. Percival G. Lowe’s journals and later his novel have helped to record a portion of the nation’s history that would have otherwise been lost. His novel will continue to capture the interest of future generations and will help many young men and women better understand their past so that they might become better prepared for their future.

- Arms, L. R. “A Short History of the NCO.” NCO Museum Staff Article. 20 Nov. 1989 Command and General Staff College. 14 Sep. 2005.

- Connelley, William E. “A Standard of History of Kansas and Kansans.” Vol. III. Chicago and New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1918.

- Johnston, J. H. III. “They Came This Way.” Kansas Historical Society. 1988.

- Lowe, Percival G. “Five Years a Dragoon.” Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press. 1965.

- Wilde, Oscar. “Quotes about History“. Thinkexist.com Quotations. 2 Dec. 2005.

You must be logged in to post a comment.